What fish can teach us about mental disorders

How outdated categories shape what we think we know — and who suffers for it

Outdated classification systems distort our understanding of biology and mental health. Today’s newsletter offers a surprising look at why some diagnostic groups may be as flawed as calling a tuna a fish.

Read on…

When we slot something into a category, our mind tells itself: That’s sorted! Onto the next. We cross it off the mental checklist.

Which can lead us to maintain those categories past their shelf life.

Consider, for instance, the fact that fish don’t exist.

In this newsletter: Linnaean classification ⁕ Darwin’s On the Origin of Species ⁕ cladistics ⁕ Lulu Miller’s Why Fish Don’t Exist ⁕ schizophrenia ⁕ Rachel Aviv New Yorker piece ⁕ DSM classifications ⁕ status quo bias ⁕ more

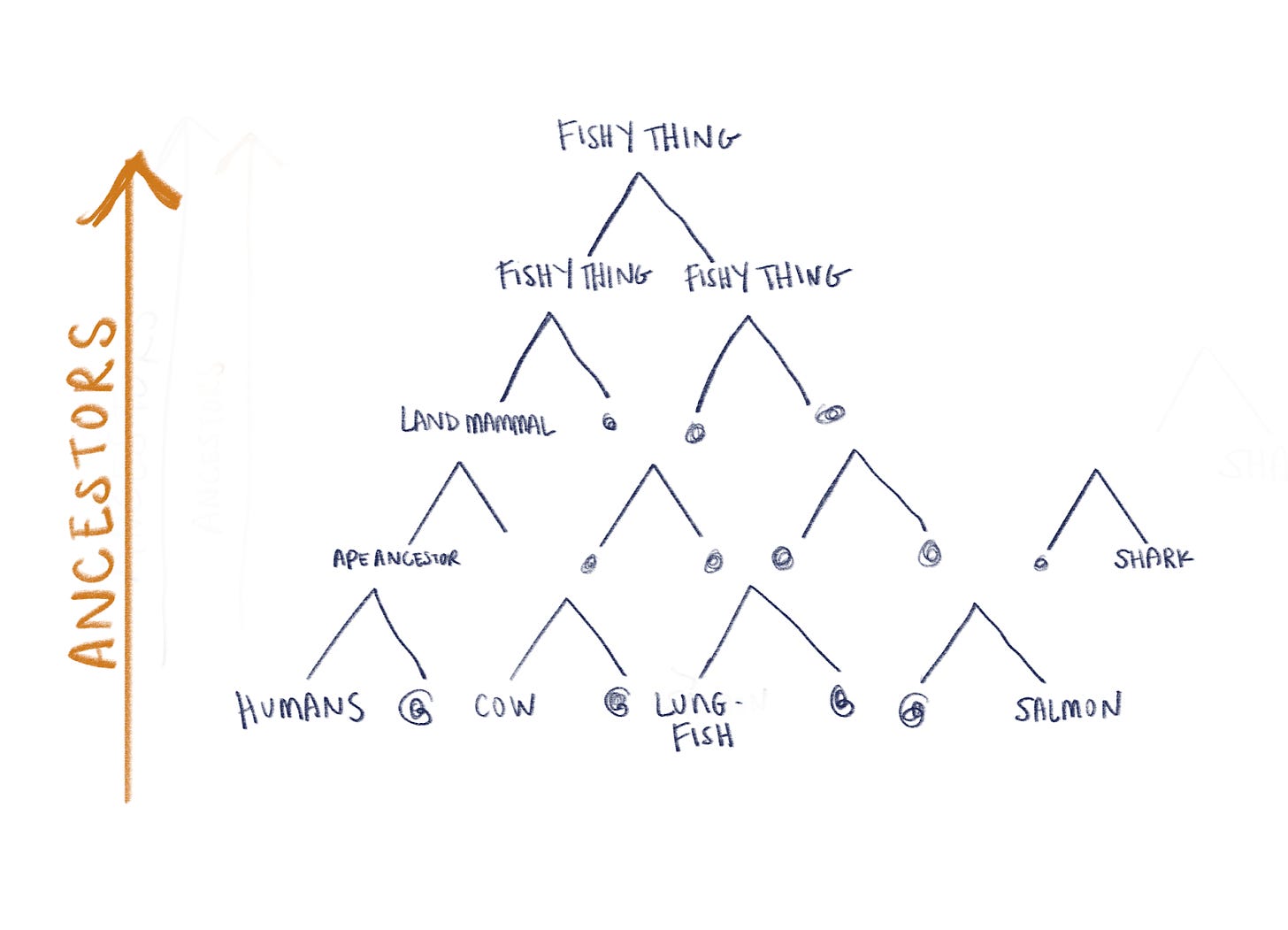

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus divided the animal kingdom into six categories: vermes (globby things like worms and jellyfish), insects, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals.

His method for classifying was based mostly on the organism’s appearance, structure, and environment. He had an extraordinarily keen eye which helped him classify, seeing things others missed.

But he also overrelied on that keen eye. He shunned microscopes and other advanced instruments. Which led his wildly influential classification system to resort mostly to surface-level comparison and contrast.

Sometimes, the durability of an idea testifies to its essential rightness. Other times, it’s a sign of our unconscious orientation toward brain efficiency: once we think we’ve figured something out, even if it’s wrong, we tend to leave it untouched.

Until someone who relies less on prior knowledge and more on sorting things out themselves, someone who takes a fresh look at our mess, comes along to shake us out of our stupor and tell us: This is not right.

Linnaeus, who predated Darwin, believed as most everyone did that God created each species with intention.

Darwin upended that idea in 1859 with his On the Origin of Species. And yet, Linnaean classification persisted with minor alterations.

Until the cladists came along. When I encountered them in Lulu Miller’s excellent book Why Fish Don’t Exist, I imagined a nihilist group of black-clad revolutionaries fit to inhabit the pages of Philip K. Dick or Asimov’s Foundation series.

Well, not quite. They’re proponents of cladistics, which is a rival approach to biological classification. Their tenet is this: organisms should be grouped according to their most recent common ancestor.

It’s an evolutionary approach, grouping species together roughly like genealogical family trees. Think about it like this: your family of origin uses your parents as the most recent common ancestors; if you extend to your grandparents, then your aunts, uncles, and cousins will form part of the group as well; if you extend to your great-grandparents, then the group enlarges with your great-aunts, great-uncles, and second cousins, etc.

The rule is that however high up you go, the group must include all descendants.

From a biological sorting perspective, this is the sounder approach. Because as we know, species can evolve parallel adaptations independently. Consider the snow hare and the polar bear. They both have white fur, but each is more closely related to other rabbits and bears than to each other.

When you take the cladistic view of relationships, surprising things emerge. Crocodiles are more closely related to birds than to turtles. An ostrich is more closely related to a hummingbird than a penguin.

And a tuna is more closely related to you than to a shark. Tuna are bony fish, and so are we (so to speak). Sharks are cartilaginous fish, a separate branch.

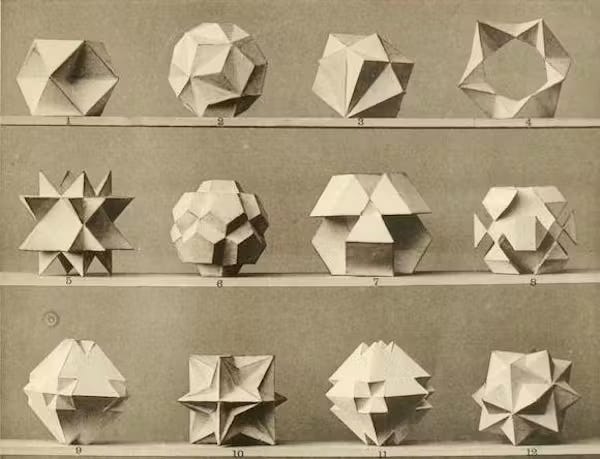

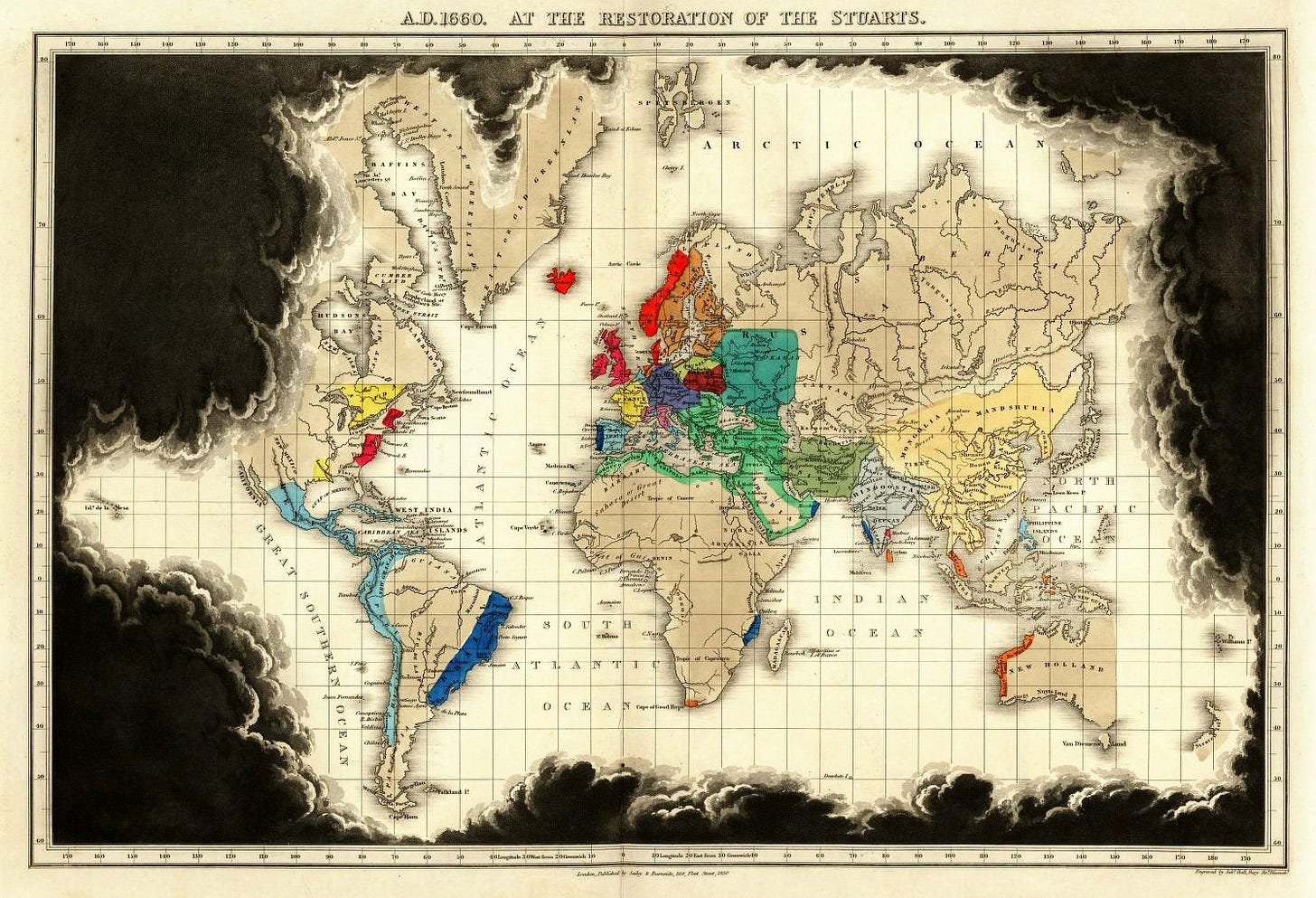

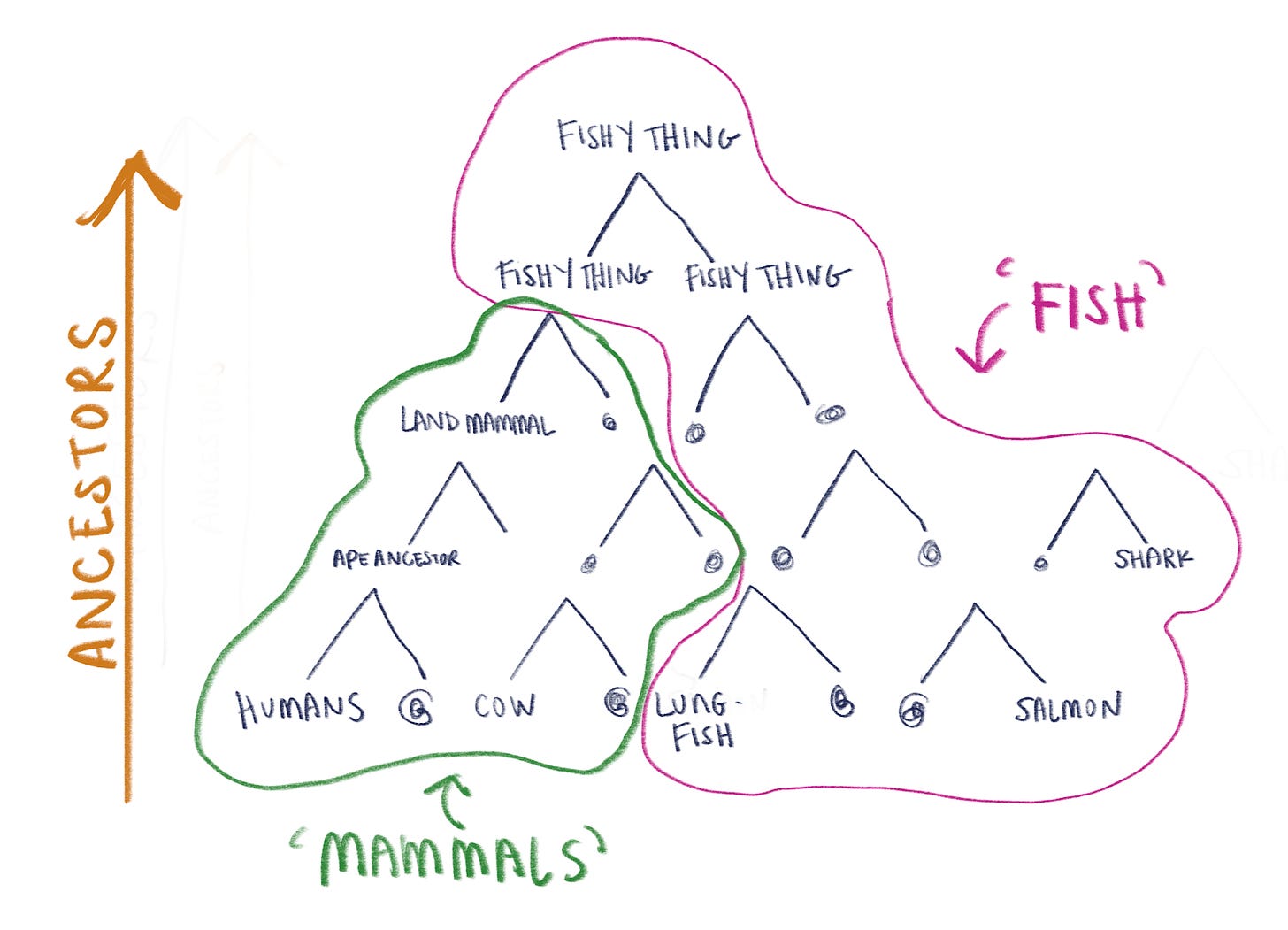

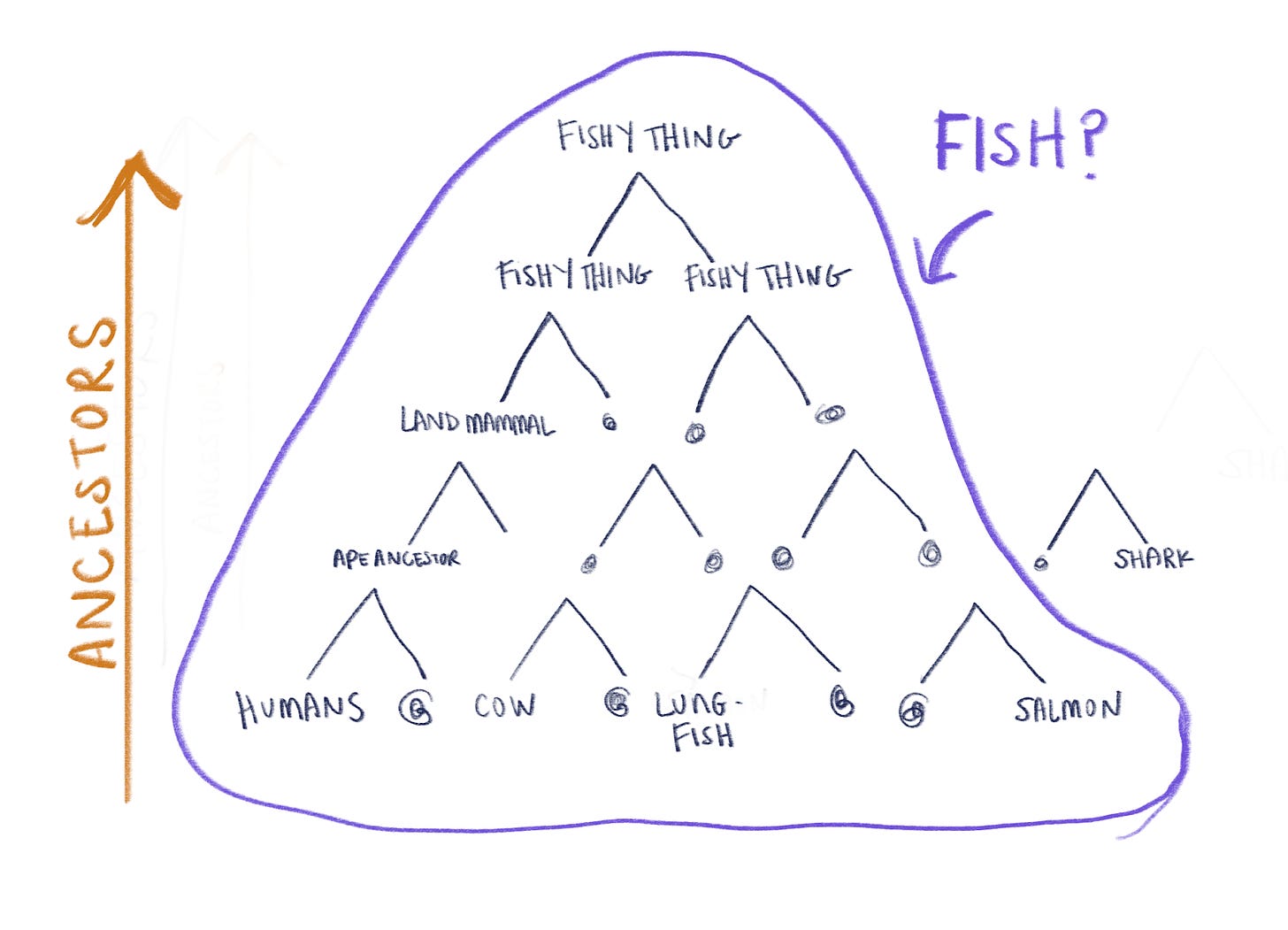

I’ve illustrated this! My first Strange Clarity illustrations.

These graphics are not scientifically accurate (as you’ll see) but they approximate 1. evolutionary branching, 2. Linnaean “fish,” and 3. cladistic “fish?”

Legend: The top of the images show the organism that evolved furthest back in time. Beneath them are the organisms who evolved from them, and so on. The curlicues are stand ins for unspecified organisms. (Again, not scientific).

Image 1: Suspend your disbelief and pretend this is a real evolutionary tree. Read it as the legend above instructs. Note that “shark” on the right is included to represent an organism who didn’t descend from the topmost “fishy thing” in the graphic. If this depiction were comprehensive, there would be upper levels for that shark tracing back a different ancestral line. But that’s superfluous. The salient point is just that the shark doesn’t share the topmost “fishy thing” ancestor in this image.

Image 2: Now we overlay the Linnaean system of classification onto our extremely convincing evolutionary tree. See how a pinch of gerrymandering is needed to approximate the traditional category of “fish,” outlined in magenta?

Image 3: Now we overlay the cladistic system. Ahh, visual coherence as a reflection of logical coherence. Feels good, doesn’t it. (That purple shape should be symmetrical… so pretend it is).

And now we’ve come to the (first) point of this essay: the category “fish” we commonly think about either doesn’t exist (i.e., it’s invalid because it doesn’t include all organisms underneath the earliest shared ancestor; it’s got that gerrymandered aspect in Image 2), or… it includes humans (as shown in Image 3).

The reason for this dramatic reveal! has its roots with Linnaeus. He assumed that because fish live underwater and have fins, they form a distinct group. But that’s just coincidental. They all happen to live underwater, and a good way to move underwater is using fins.

It’s trippy. What helped me understand this false-fish notion is this: All life on earth began in water and remained there for 3.2 billion years!!!

So before anyone awkwardly lumbered onto land, there was massive evolution happening underwater. Distinct branches developed. When members of a given branch became landlubbers, they remained more closely related to fish within their branch than to other landlubbers sprung from other undersea branches. And vice versa: certain “fish” are more closely related to landlubbers in their evolutionary branch than to fellow swimmers.

What’s also trippy is that I didn’t know any of this until I read Miller’s book. That strikes me as wild. It’s like still thinking Pluto is a planet, but worse.

The fact that a salmon is more closely related to a cow than a shark, and a tuna to a human than a lamprey, may be academic for most of us. We’ll still talk of “fish” in the classic sense and everyone will know what we mean. Even my illustrations perpetuate that longstanding idea, since I talk of “fishy things” and mean it traditionally.

So, the fact that “fish” isn’t a distinct group is interesting but not, for most of us, life-changing.

Unless, perhaps, you’re a pescatarian.

Darwin introduced evolution to the world in 1859. Why did it take a century for an evolution-based approach to taxonomy, for cladistics, to emerge?

Maybe because we like to move on when we think we’ve figured something out, so as to use our energy elsewhere. We have a bias toward existing systems — sometimes called status quo bias, after a foundational paper from 1988 by William Samuelson and Richard Zeckhauser. Even when those systems are supported by weak evidence or have fairly apparent structural defects.

The authors of that 1988 paper plucked an epitaph from Samuel Johnson: “To do nothing is within the power of all men.”

At that, we excel.

But what, if anything, does this have to do with schizophrenia?

A woman named Mary developed symptoms in adulthood diagnosed as schizophrenia. Her daughters describe turbulent, unstable childhoods in their mother’s house. Mary would construct an elaborate barricade at their apartment door, so the girls had to allot extra time to get to school in the morning. She’d accuse her older daughter of poisoning her pizza. Their mother lived in a different reality. One to which they couldn’t build an emotional bridge, leaving them feeling, in some ways, motherless.

They’d sought professional help for her, and Mary was even institutionalized once. But she was part of the one-third of diagnosed schizophrenics for whom antipsychotics have no effect.

Then, as Rachel Aviv explained in her New Yorker piece telling this story, Mary was diagnosed with cancer and treated with chemotherapy and an immune suppressant, rituximab. Her daughters thought she was dying; they prepared themselves for her passing.

But Mary didn’t die. The cancer cells were eradicated. And something else: she began to speak more clearly, be more alert and present in conversations with her daughters. Just as the cancer cleared, so too did Mary’s schizophrenia symptoms.

She’s one of a number of people whose treatment-resistant schizophrenia disappeared after taking immunosuppressants.

Like the others we’ve discussed, the DSM is also a classification system: a taxonomy of “mental disorders.” It was built on a legacy of observing behaviors and shuffling them into categories of disorders, so it’s closer to Linnaean classification than to cladistics. Mostly, it’s concerned with what’s happening at a person’s surface. Their observable state.

Which is sort of like creating a group called “fish” based on scales and fins.

This approach can paper over important differences in origin or internal mechanisms leading to that observable state.

Anxiety illustrates this. Initially, the DSM treated anxiety as a singular disorder, called Anxiety reaction (and rooted it in a Freudian belief that it resulted from unconscious mental conflict). Subsequent editions began to distinguish different disorders that featured anxiety: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Phobic disorders (like agoraphobia), Separation anxiety disorder, and Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Anxiety is a common feature of all, but these are vastly different disorders that were initially lumped together.

Not all disorders in the DSM have been permitted to branch in this way. Some are still stuck in monolithic, overbroad classifications.

In June, I wrote about research indicating that narcissistic personality disorder is an imprecise, or even invalid, category. From that research, I offered a caution:

What we currently label as a single disorder may turn out to be multiple, distinct conditions that never should have been grouped together in the first place.

Schizophrenia, it appears, suffers the same flaw. Like Anxiety reaction, the DSM classifications of Narcissistic personality disorder and Schizophrenia may depend on surface-level similarities that are merely coincidental, emerging from distinct conditions or origins.

The fact that Mary’s symptoms cleared after taking immunosuppressants suggests that she was never schizophrenic in its traditional sense of a disorder with a genetic basis. Instead, she had an autoimmune disorder whose symptoms resembled schizophrenia.

Her case is not a one-off. There have been others, as reported by Aviv:

A 2017 study in Frontiers in Psychiatry described a woman with a twenty-five-year history of schizophrenia. She also had a skin disease, for which she was given drugs that reduced inflammation and suppressed her immune response. Her doctors noticed a pattern: when they treated her skin lesions, her psychosis went away. They hypothesized that the rash and the psychosis had been caused by a single autoimmune disorder, and were cured by the same drugs. Another paper in Frontiers in Psychiatry described a man with “treatment-resistant schizophrenia” who developed leukemia. After a bone-marrow transplant, which reconstituted his immune system, he startled his doctors by suddenly becoming sane. Eight years later, the authors wrote, “the patient is very well and there are no residual psychiatric symptoms.”

For the one-third of schizophrenia patients who don’t respond to traditional treatments: what if they don’t actually have schizophrenia?

It’s past time to hold the DSM’s approach at arms’ length. We can’t simply ignore it, since right now there’s no better alternative. But like Linnaean classification, it rests on a flawed methodological base. One developed in the early 1900s, innovative at the time but long since past its sell-by date.

The step-wise modifications made with each new edition of the DSM just aren’t enough to correct that flawed base. A cladistics-like transformation is needed.

Because all the while, people are suffering from being lumped in with diseases or disorders they don’t have. Think of all that lost time for Mary and her daughters.

The cladistics framework is based on biological evolution, which doesn’t map onto mental disorders.

So we need to ask: what’s the mental disorders version of cladistics? What’s a better approach? I don’t have the answer. But it’s a question we should pursue with relentless focus.

Fortunately, efforts are underway. In 2023, the Stavros Niarchos1 Foundation (S.N.F.) Center for Precision Psychiatry and Mental Health was founded at Columbia University through a $75 million grant. Its mission is to research “the biological causes and underpinnings of mental illness and discover treatments for alleviating suffering from conditions previously considered untreatable” — like the misdiagnosed schizophrenia of Mary and so many others.

As well, the S.N.F. is focused on “closing the gap between research and clinical practice.” Thank the lord. Clinicians still have misguided ideas of what autism is, leading to unscientific diagnostic decisions. And the DSM, that clinician bible, still focuses on only two umbrella traits of autism, when researchers have long understood that our traits are far more sweeping and complex.

To conclude: both concepts — “fish” and “schizophrenia” — provide cautionary tales.

What do we miss when we rely on old frameworks? It’s difficult, even impossible, to tell while working inside them.

Which makes it all the more important to hold firmly onto epistemological humility — a fancy way of saying, being humble about our ways of knowing — and lightly onto everything else, including what we think we know for sure. And to listen to people who offer tough, but good-faith, criticism of conventional wisdom.

And also: for the love of all that’s holy, can we please do something about the DSM?

P.S. Yesterday, I read with delight a new reader comment by Shannon Barrera of Build With Care, knowing this post would come out today. Shannon anticipated today’s themes when she wrote:

But more importantly, I think the whole framework used to define autism as a disorder of “deficits in social communication” and “restricted, repetitive behaviors” is sort of comically inaccurate. It’s like describing the shadow of something and thinking you’re describing the thing. It reduces autism to the traits that can be observed from the outside, while completely ignoring the internal experience of being autistic.

That’s beautifully put: “describing the shadow of something and thinking you’re describing the thing.” Thank you, Shannon!

Did you enjoy this post? Ways to support my work—for free!

1. Leave a comment and 2. Like this post by tapping the heart to help others discover it.

Looking for more to read? Check out these past posts:

Stay curious,

Laura

Probably not that Stavros Niarchos but one of the other Stavroi Niarchoi (of whom there are at least three).

So interesting! It is crazy how often diagnoses result from the external effect of someone's mental disorder instead of what's happening internally. "You can't be autistic because you have friends" yeah and I literally can't eat vegetables unless they're blended into a soup, both can be true lol

I read Why Fish Don't Exist in my book group a few years ago and loved it, because I'm a sucker for epistemological revolutions, and the Cladistics people really pulled it off. And it's kinda funny, too, as you mention: I will know this stuff, but then when I'm thinking of eating fish: they're all just "fish" - even at a sushi restaurant. Unagi/eel...I even ate octopuses until I found out how intelligent they were. Why did I react that way to intelligence?

I often think about the level of scientific knowledge. We know an astounding amount. But I suspect it's closer to 1% of what can be known, and not 99% that some think. I think we hardly know anything. I know I don't know much at all.

I love how you linked cladistics to the DSM. It's really witty and smart and...intelligent. Thank you!

I had a brother who had schizophrenia. He died of an asthma attack just before he would turn 40. The schizophrenia didn't kill him, but he wasn't able to think clearly and get his rescue inhaler refilled.

He heard voices so intrusively in his consciousness that "they" would interrupt our conversations. When he was diagnosed I read 80-100 books on schizophrenia. 1908: Bleuler called...whatever this was..."schizophrenia": etymologically "split mind." The mind is NOT "split" in any meaningful way, though. But still, "they" "have" "schizophrenia." No, they have a bunch of specific neurobiological imbalances (<---- there's another problematic metaphor, I know!) that seem to be related, that cause them to, quite often, lack insight into their own dis-ease.

I followed those stories about treating people for an entirely different thing and they become more lucid. I taught myself to not get too excited. But maybe there finally is hope for effective treatment now. Maybe. It was a nightmare to deal with my brother. One heartbreak after another.

And the clinicians are just going with what they learned in medical school. We can hope for a Clade group for mental disorders, can't we? I know it has to do with origins - they once thought they'd find "the" gene that caused schizophrenia. Then they did!..

...But then they found another one linked to that dis-ease, on another chromosome. Then another one on another chromosome. That it's not an OGOD disease: One Gene, One Disease, was a tough pill for me to swallow back then. But I think there's hope. I hope there's hope. Is there hope?