Biography and the temptation to make things up

How life-story telling can betray the figures it aims to reveal

History has been misread through a neurotypical lens.

That’s the central thesis of a book proposal I’m working on, which proposes to examine misreadings of historical figures and promote greater nuance in depicting different kinds of minds.

I’ve got the deep research part of the equation covered (oh boy do I). But I know nothing about writing biography, even though I’m proposing to write a dozen side-by-side profiles of historical figures. How does life writing work? Where do I start? Not with birth for every one of them, surely.

I’m not a just wing it! kind of person. So rather than plunge in, I set out to study the art of biography itself. This has been a useful detour because in the process I’ve sharpened why I think this project is so important.

How biography began

There are countless books on writing fiction, memoir, screenplays, but comparatively few on biography. For such a popular genre it’s a surprising gap. What is biography? Why does it matter? What are the rules and how might they be broken?

My self-education started with Hermione Lee’s Biography, A Very Short Introduction. Lee is a celebrated biographer, mostly focusing on other writers like Virginia Woolf, Elizabeth Bowen, Philip Roth, and Tom Stoppard.

To start, Lee offers a simple definition of biography: “the story of a person told by someone else.” A story, not an “account,” because “biography is a form of narrative, not just a presentation of facts.”

(Which is what scares me. I’m good with facts and research. I’m a lawyer; I can assemble a compelling case. But the storytelling aspect? I can’t even tell a joke.)

Biography has its roots in the ancient stories of exemplary figures, Lee tells us. These stories were designed to instruct, to model, to awe: the accounts of the Egyptian Pharaohs; the titanic profiles in the Old Testament. Although there are exceptions, these were mostly one-dimensional.

Noah, of Ark fame, is presented as a singularly righteous person but says almost nothing and displays little interiority. He obeys, builds, survives, gets drunk. (“When he drank some of its wine, he became drunk and lay uncovered inside his tent.”)

Next came the classical life-story tellers, Herodotus and Suetonius, who added more shape. And then the hagiographers who backtracked to flatness. Hagiographies are lives of saints, meant to prove their holiness; the goal wasn’t to depict a real person but to outline a holy model.

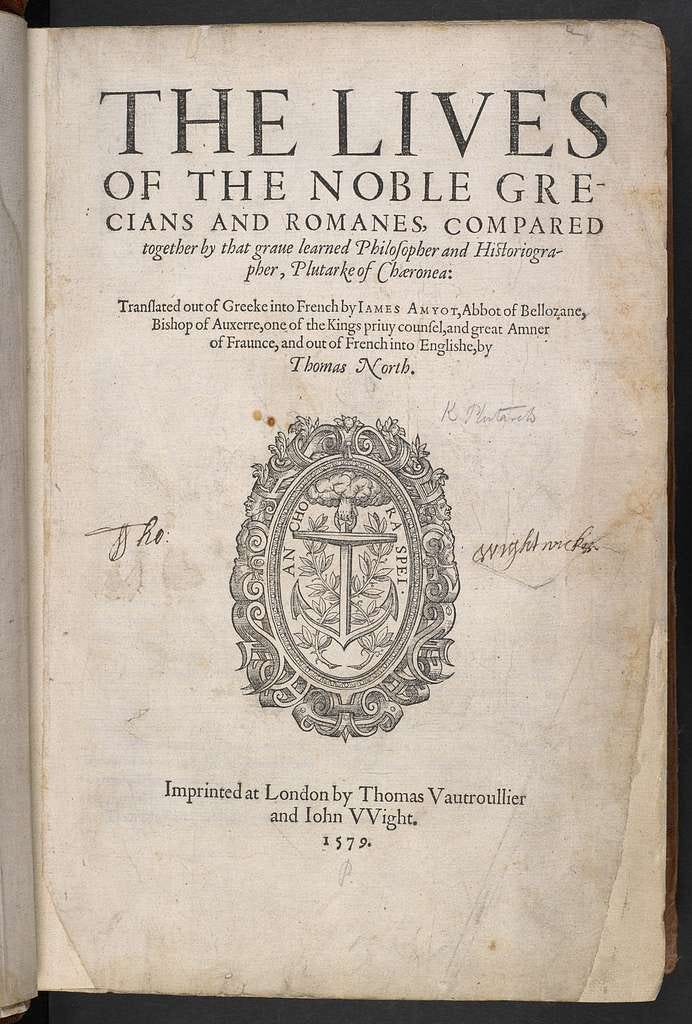

Our modern form of biography was really born with Plutarch (40-120 CE) and his Parallel Lives. It features 23 paired profiles (46 total), of figures like Alexander the Great and Cicero. They are presented in pairs to invite comparison and contrast.

“I am not writing history but biography,” Plutarch explained. He argued, for the first time, that the big events of a life—“the most outstanding exploits”—were not the most illuminating. “Often, in fact, a casual action, the odd phrase, or a jest reveals character better than battles involving the loss of thousands upon thousands of lives.”

One such detail: Plutarch recounts in his Life of Solon that when the dramatist Thespis claimed that inserting lies into his tragedies was harmless play, Solon struck his staff against the ground and warned, “If we praise and approve of such jests as these, we shall soon find people jesting with our business.”

It’s a moment of theatrical protest that reveals Solon’s black-and-white thinking, his discomfort with artifice, and his belief that invention, once permitted, will not stay bounded—a concern that resonates with the liberties some biographers take. I’ll come back to that soon.

Whereas the early life stories turned mortals into larger-than-life figures, Plutarch did the reverse: he cut legendary figures down to size. He stripped men of “the pageantry of life,” John Dryden wrote in his 17th-century life of Plutarch. “You see the poor reasonable animal, as naked as nature ever made him; are made acquainted with his passions and his follies, and find the Demi-God a man.”

(In a powerful parable of biography’s impact, Plutarch’s Lives helped Frankenstein’s monster break through his own one-dimensionality into a fully-fleshed being).

“Catching a likeness”

Biographers often analogize their work to portrait painting.

If a dozen artists paint the portrait of the same studio model, you get a dozen distinct images. Each artist makes countless choices: which parts of the face to render in detail, how to interpret the sitter’s expression, what style of brushwork to use, and so on. And there are also unconscious decisions, produced by the limitations of their abilities or their unexamined point of view.

The end result is one depiction among an infinite number of possibilities. Success lies in whether the depiction reveals some truth. Not the whole truth—that would be impossible—but enough to find meaning.

“Catching a likeness,” is how Lee phrases the aim of the biographer. In 1814, William Hazlitt wrote that “portrait-painting is the biography of the pencil.”

What biography is today

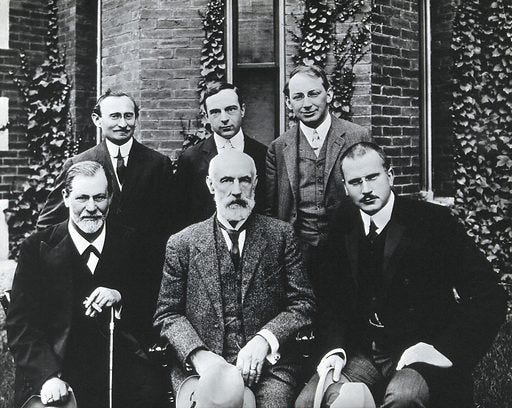

Biography evolved from its one-dimensional focus on actions alone to address psychology, too. This started with Plutarch but took off in the 20th century, when Freud began his interrogations of mind and subconscious. “Western biography from this time has more to say about contradictions and fluctuations in identity, and about the unknowability of the self,” Lee says.

And so, biography has evolved alongside psychology and the social sciences, as tools for understanding character have grown more nuanced.

Today biographers wrestle with the why of the person; the fundamental puzzle of nature versus nurture. Was the person always going to be this way? Or were they formed, as Lee puts it, “by accidents, contingencies, education, and environment”? Of course it’s not an either/or proposition, and the work is tracing the confluence of factors that make the person who they are.

Biographers today, in my view, tend to overrate nurture and underrate nature—a tendency that reflects a broader cultural belief in our own agency. You see the same impulse in the early days of autism research, when “refrigerator moms” were blamed for their children’s perceived coldness and self-containment. And it persists today in the resistance to autism’s genetic basis: the insistent search for an external cause that might, by implication, offer a means of prevention. We fear that something so fateful might lie outside our control.

When biography fakes it

I say what I mean, and I run into trouble because I assume others do the same. I take what people say literally.

Until fairly recently, I thought that if historical nonfiction or biography uses quotation marks to set off a person’s speech, then the person really uttered those words.

I only realized this wasn’t necessarily the case when my practicality overcame my gullibility: I’d read conversations for which there is no transcribed record, or details of mundane events that have no original source.

I’m uncomfortable with this fabrication. On the one hand, dramatization makes for a more entertaining read, and imagined dialogue can have a “ring of truth.” But how does the biographer ensure that they’re toeing the line? That they aren’t venturing into mere fantasy?

I have a particular objection when such embellishment isn’t signaled in the text.

Here’s an example, from Carole Angier’s Jean Rhys: Life and Work (1985), describing a scene where a teenage Rhys goes school clothes-shopping with her aunt in London, where Rhys spots:

an elegant three-quarter length coat and a grey fur collar. “Oh do let me have it,” she pleaded – but silently, inwardly. “I will be so different if you do, you’ll like me better, oh I must have one pretty thing . . . .” But the price ticket said twenty-five guineas. “Not at all suitable,” Aunt Clarice said; and chose one for four guineas instead [...] Jean said nothing, but she was heartbroken. How could she appear before a lot of strange girls in such a hideous thing? “They’re bound to dislike me,” she thought.

Flipping through Angier’s references, I don’t see any source for these specific thoughts, and they didn’t feature in Rhys’s autobiography, which I’ve read. From my extensive readings of Rhys, these imagined thoughts about the fur coat clang like discordant notes. They don’t sound like her.1

Another example, from Stephen Backhouse’s Kierkegaard: A Single Life (2020), depicts an undated scene at a popular cafe fronting a Copenhagen square, where two old grandees sat people-watching:

They did not see Søren coming, but as this odd man lurched by their table, arm outstretched to order his third coffee of the day to go with his fourth cigar, they would have been jostled.

Really? There can’t possibly be a record that on this particular day these two old farts were “jostled” by an unseen Søren. This is less problematic because it doesn’t invent thoughts, but I still find it distracting.

The proper boundaries of invention

Perhaps it’s my literalness that makes me uneasy. But I’m not the only one who values an accurate story over an entertaining one.

I have company in Jean Rhys herself, the subject of the first biography sampled above. The editor’s foreword to Smile Please (1979), Rhys’s autobiography, explained that Rhys insisted on accuracy at the expense of breadth:

In a factual account she would have to rely on memory, not instinct, and this alarmed her. Her honesty was uncommonly strict, so she felt that the only dialogue she could use in such a book would be that which she was perfectly sure she remembered exactly.

Rhys’s approach to autobiography was not typical, so this offers rich insight into how her mind worked. A counterpoint: Ford Madox Ford, Rhys’s novelist mentor (and onetime romantic partner), was known for crafting legends about himself that he carried forward in sensationalized “autobiographies.”

Seat me on the Rhys side of the aisle.

Yet I’ve learned that a biographer doesn’t have to choose one or the other: entertainment at the cost of integrity, or integrity at the expense of telling a good story.

Although some biographers adhere strictly to primary-source documentation, others allow for limited reconstruction if the speculation is clearly marked. For instance, signposting with “she might have felt…” or “perhaps…”

Signposting seems essential if you’re going to invent. Otherwise the reader is left to puzzle out what’s based on evidence and what’s imagined. Maybe that’s a simple task for some, but for those who—like me—have a tendency to take things at face value, we might be misled.

Lee’s book mostly avoids being prescriptive as to how biography should be written, but she comes closest when the topic of invention comes up.

“Plenty of biographers dramatize their narratives with descriptions of emotions, highly-coloured scene setting, and strategies of suspense.” But it can go too far, Lee writes:

Some biographies read more like fiction than history. This can attract readers, but can also give the genre a bad name. John Updike once remarked that most biographies are just “novels with indexes.”

For Lee, the harm extends beyond marring the genre’s reputation. “Untruths gather weight by being repeated and can congeal into the received version of a life, repeated in biography after biography until or unless unpicked,” she cautions.

I’ve seen this dynamic in a frequently told story about Rhys and two dolls: one “fair,” one “dark.” A biographer interpreted the dark doll, given to Rhys’s sister, as a Black doll—despite no textual support for that reading. In fact, the dolls likely mirrored the sisters’ appearances: Rhys had light coloring; her sister was dark-haired, suggesting that the dolls were chosen to match the girls. Rhys wanted the dark doll, and when she didn’t get it, she smashed the fair one’s head with a stone. From this, the biographer inferred that Rhys was violently rejecting her whiteness from a desire to be Black—a speculative reading built on a false premise. If anything, the episode suggests a revolt against her alienation within the family unit: Rhys was the only blonde in the dark-haired family. She was also the only one of five children who was socially inept and “alien,” which singled her out for harsh treatment. That she was the only one with light hair was symbolic of her more essential divergence.2

The biographer should resist the urge to gap-fill with invention, Lee says. When the historical record is spotty, “then the true story would have to take the form of unanswerable questions or gaps in the records.”

Toward a new way of reading lives

The problem I’m pinpointing here gives me confidence in my purpose. As I wrote at the start, my strong belief is that history has been misread with a neurotypical lens. This misreading can then be compounded if invented thoughts or words are attributed to a subject, based on assumed neurotypical thinking patterns.

My project shines a spotlight on the problem of assuming neurotypicality when examining history. I seek not only greater fidelity to individual minds but also to surface the buried assumptions that have historically carried life-story telling.

I will be clear that in my profiles, I’m offering neurodivergent readings. The reader can agree with those readings or not based on the evidence I present. The important thing is to be transparent, to bring subtext to the level of text.

Why should anyone care?

In a book proposal workshop I’m in, we’re asked repeatedly to justify our projects. Why should anyone care? Why is this book needed?

It’s a critical exercise that pushes us to be precise about our aim and the surrounding stakes.

I’m currently reading a collective biography that I picked up for inspiration, but have found myself utterly absorbed by.

It’s Jane Austen’s Bookshelf by Rebecca Romney, an exploration of the forgotten women writers who inspired Austen. In an early chapter, Romney reflects that themes from Evelina, an 18th-century novel by Frances Burney that Austen loved, surprisingly echo moments of Romney’s own modern coming of age.

Romney writes:

This is why we continue to read books centuries after they were first published: not because they have reached some subjective standard of ‘perfection,’ as some critics like to suggest, but because they still have something to say that is meaningful to us.

I underlined these words. They apply equally to biography, I think. We continue to care about lives—imperfect lives—centuries later because they reveal meaning in the present day.

My project is to recover the meaning that has been distorted or lost when lives are read through a neurotypical lens.

Tell me in a comment: What’s the best—or most recent—biography you’ve read? What do you look for in biography, and what irks you?

Did you enjoy this post? Please support for my work (for free!): Subscribe for regular updates and tap below to heart this post so others discover it.

Looking for more to read? Check out these past posts:

I don’t want to critique Angier too much! She wrote a nearly 800-page biographical tome that’s highly regarded. Her contributions to our understanding of Jean Rhys are unparalleled.

My source for Rhys’s distinct appearance from her family members is Miranda Seymour’s recent biography I Used to Live Here Once (2024): “Pale-skinned, sapphire-eyed and exceptionally sensitive in spirit, [Rhys] resembled neither of her parents, nor her more heavily built and dark-haired siblings. Almost from birth, […] she felt like an outsider; a changeling; a ghostly revenant in the hard light of day.”

Laura-

The mere idea of hammering home to readers that we've only recently realized how basically all biographies were written assuming neurotypicality (<----is that even a word?) and that there's no doubt much more neuro-atypicality in history's biographical subjects seems like a fascinating project.

When I ponder this project the first thing I think of is the weight of research needed to turn a subject into something fresh. Maybe I don't fully understand this project. EX: I've read a lot about Joyce and Pound. There are triangulations I go through as I read about these writers through the lenses of different biographers. For one: they're both very rich, strange characters. Almost all the biographical writing about them was done by writers who I doubt were thinking about the semantics of "neurotypical." That both Pound and Joyce were weird is obvious from their own writing. I find when I read about these two figures that I'm paying attention to what was included vs. what was left out. But these two examples might be bad ones for your project, as, for just one example: they're closer to our time and so there's much more data to reference: letters, books of "I was friends with James Joyce", "Here's a chronicle of the people who hung out with Pound when he was detained for insanity at St. Elizabeth's Hospital", etc.

The second thing that comes up for me, here: the defense of scholars and their adherents when someone tries to say something new about a famous figure. Lots of resistance there. So I'm forever looking for divergent takes on, say, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. And they're there! There's quite a lot of minority scholarship on these guys. Was Jefferson really that much of a snob? Was Franklin blinkered by Enlightenment fetishism over "reason"? Did Washington not only grown that hemp crop but separate the males from females so he could smoke some of it and get high, probably to deal with dental pain? Etc.

In the Western "canon", after Plutarch, often the Big Book that comes up biography-wise is Boswell's Life Of Johnson. Boswell, by his side for many years, and Johnson is very strange and wonderful, but Boswell has zero modern-day vocabulary for our modern psychological categories. In some sense, we always were neurotypical, but didn't have the words for it?

I tend to think our collective historical memory/knowledge can't possibly be as fleshed-out as it "really was." That is: there was far more non-neurotypicality than most books let on. But how to persuasively show this? It can be done. And should be done.