The Collection of Collections

(July 25, 2025) A lot of my curiosity relates to collecting and collections. I started this Substack in part to collect my thoughts—a dedicated place to archive my mental wanderings so I can revisit and add to them (and also not forget them).

Another lifelong obsession has been studying people. Mostly dead, but some alive. And the sort of people I study often have collections themselves. As well, I’m drawn to stories about collections.

I’ve started to note when collections come up in my readings. And why not share them here? I’m curious to see how miscellanic and/or unwieldy this gets.

Here’s my Collection of Collections: a living archive.

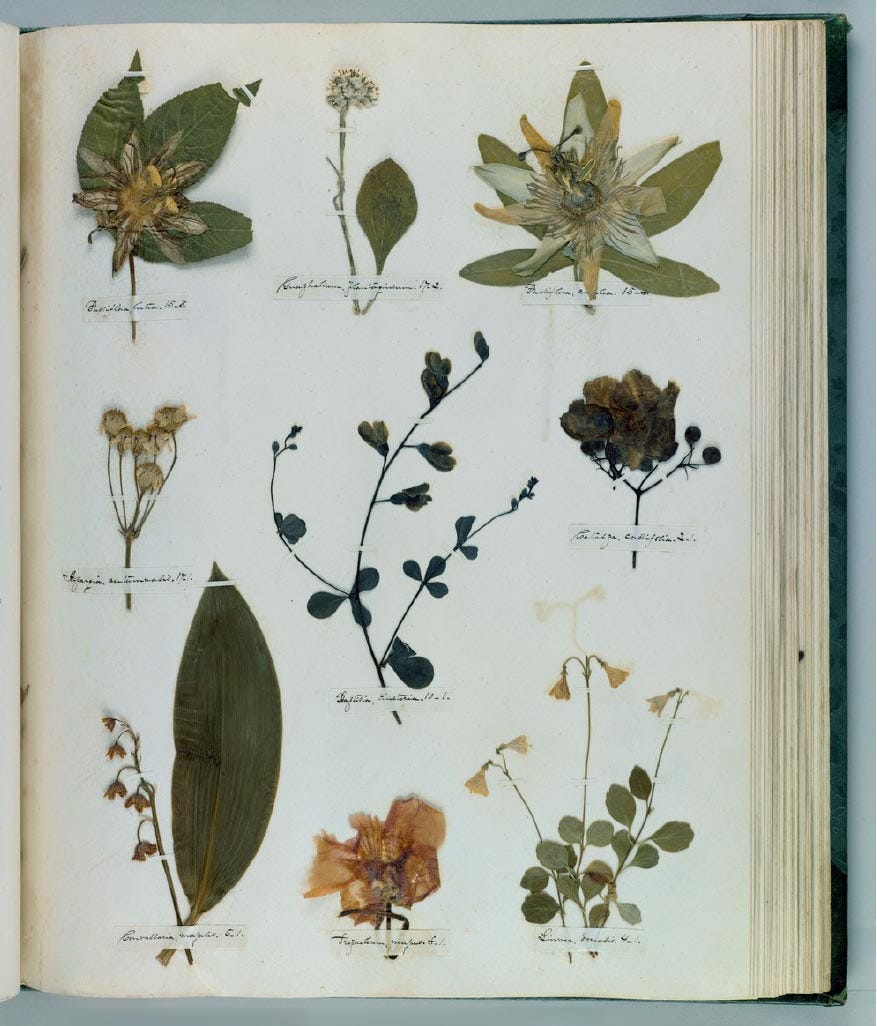

Herbariums / Herbals

In the Victorian era, maintaining herbariums was the hot thing to do—a rare global trend in a pre-digital age. The practice features in Polish Nobelist Olga Tokarczuk’s incredible novel The Empusium, called an “herbal” by the protagonist, which is where I first caught a glimpse of its cultural importance in the 19th century.

The poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) maintained two collections: the first, her handsewn booklets of poems (discussed below), and the other, her herbarium, begun in childhood. Using a dark green leather volume manufactured for this purpose, Dickinson pressed 400 to 500 plant specimens between its pages. At age 14, she wrote a friend: “I have been to walk tonight and got some very choice wild flowers.” “Have you made you an herbarium yet?” she went on to ask. “I hope you will if you have not, it would be such a treasure to you; ‘most all the girls are making one. If you do, perhaps I can make some additions to it from flowers growing around here.” (First discovered in My Wars Are Laid Away in Books, The Life of Emily Dickinson, by Alfred Habegger, 2002).

Found objects

Starting in the 1960s as Paris saw a flurry of municipal modernization, Roxane Debuisson (1927-2018) began collecting cast-aside Parisian construction detritus on her daily walks: “rating plates, bench marks, pieces of bridges, tree corsets, street signs, fountains, gallows, Métro seats, mailboxes, and some seventy thousand commercial invoices.” As Lauren Collins of the New Yorker tells it, a visitor to her apartment “could walk through corridors hung thick with shop signs—a cobbler’s boot, a glove-maker’s hand, a six-and-a-half-foot-tall pair of scissors, two gilded snails—into the dining room, where an entire wall was given over to a set of enamel-and-glass panels from a defunct pâtisserie.” (First discovered in “The Case for Lunch,” New Yorker, July 21, 2025).

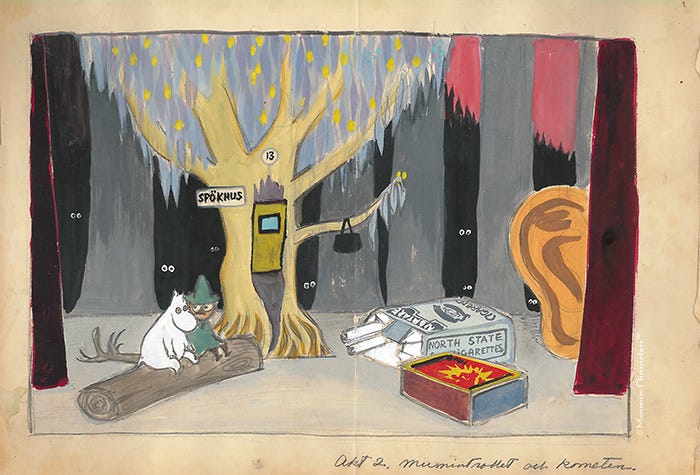

Personal Archives

Some people create highly organized, even obsessive collections of their own work.

The artist and writer Tove Jansson (1914-2001) (an obsessive figure for me; I’ve written about her here) carefully archived her multidisciplinary work and life ephemera, starting with her childhood drawings and diaries. Her biographer gained access to this trove of “masses of notes, manuscripts of stories and talks, lists, drafts, sketches, drawings, plans for projects of various kinds, photographs, diary notes, cuttings, articles, every kind of letter and correspondence, programmes, catalogues, and so on.” Both “personal” and “strictly documented,” it provided a “picture of the writer and artist who built up this large memorial to herself and her work.” (First discovered in Tove Jansson Life, Arts, Words, by Boel Westin, trans. Silvester Mazzarella, 2013).

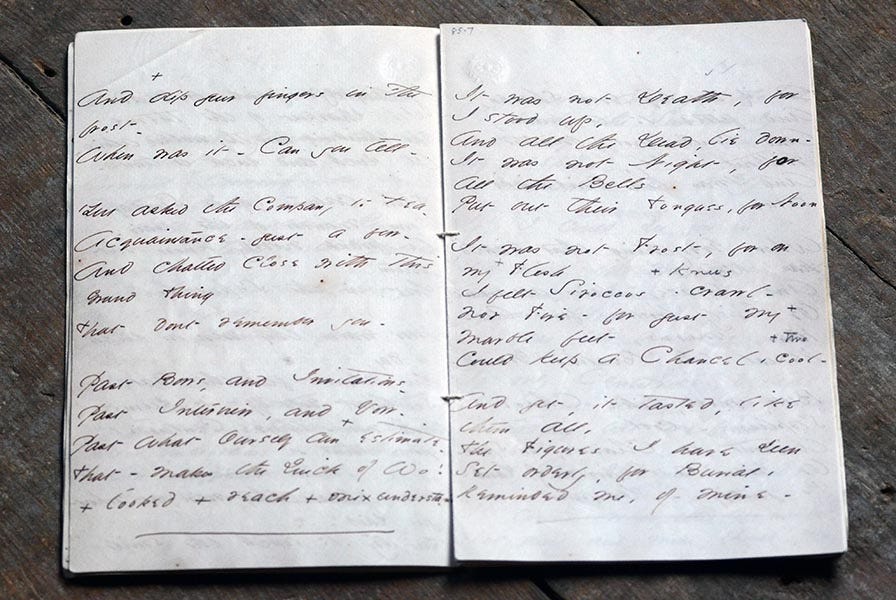

Dickinson’s poetry booklets are called fascicles by scholars (source: Emily Dickinson Museum) The poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) (another figure of obsession, I’ve written about her here) stitched her poems into little booklets with needle and thread. No one knew about their existence during her lifetime, but we now see they were alluded to in poems like “Essential Oils — are wrung —,” which explored a metaphor for poetry that was kept in a drawer. After her death, her sister found the poem booklets in a drawer in Dickinson’s bedroom, and contrary to Dickinson’s legal instructions to burn all her papers, these poems were published—the reason we can read Dickinson’s work today. (First discovered in My Wars Are Laid Away in Books, The Life of Emily Dickinson, by Alfred Habegger, 2002).