Living with contradiction: Tove Jansson’s wartime diaries, and ours

What a Finnish artist’s midcentury journals teach us about ambivalence and endurance

This post has been sitting in draft for a little while. I kept hesitating to hit “publish.” It’s one thing to say these things privately; another to say them publicly. I’m admitting that I’m not always brave, and I don’t always have clarity of vision. Most of the time, I’m observing from the sidelines, offering only financial support for the things I care about.

Still, I decided to share this as an honest reflection of where I am — and how I feel — with the sense that I’m probably not alone.

My life runs on two planes. On the surface there are the rituals and logistics of daily living: ordering socks, snuggling kids, RVSP’ing (late) to birthday parties, watching streaming TV, forgetting to walk the poor dog. This is the domain where things are generally fine. It’s hard raising young kids but in a specific, temporary way.

Underneath is a slow-moving, cold current of dread. I have a constant, general worry about things I have no control over: the planet, my children’s futures, the way people seem to be OK with misery on a mass scale so long as it doesn’t touch them. I’m not always conscious of this current but it’s continuously there, shaping my thinking.

The other day while drawing, my daughter said, “I want to be an artist when I grow up.” I smiled and told her that was awesome. Then I thought: What will the world look like when she’s grown? What kind of choices will she really have?

I think lots of people are feeling this heaviness but hide it beneath the regular interactions: How was your weekend? Doing any travel this summer?

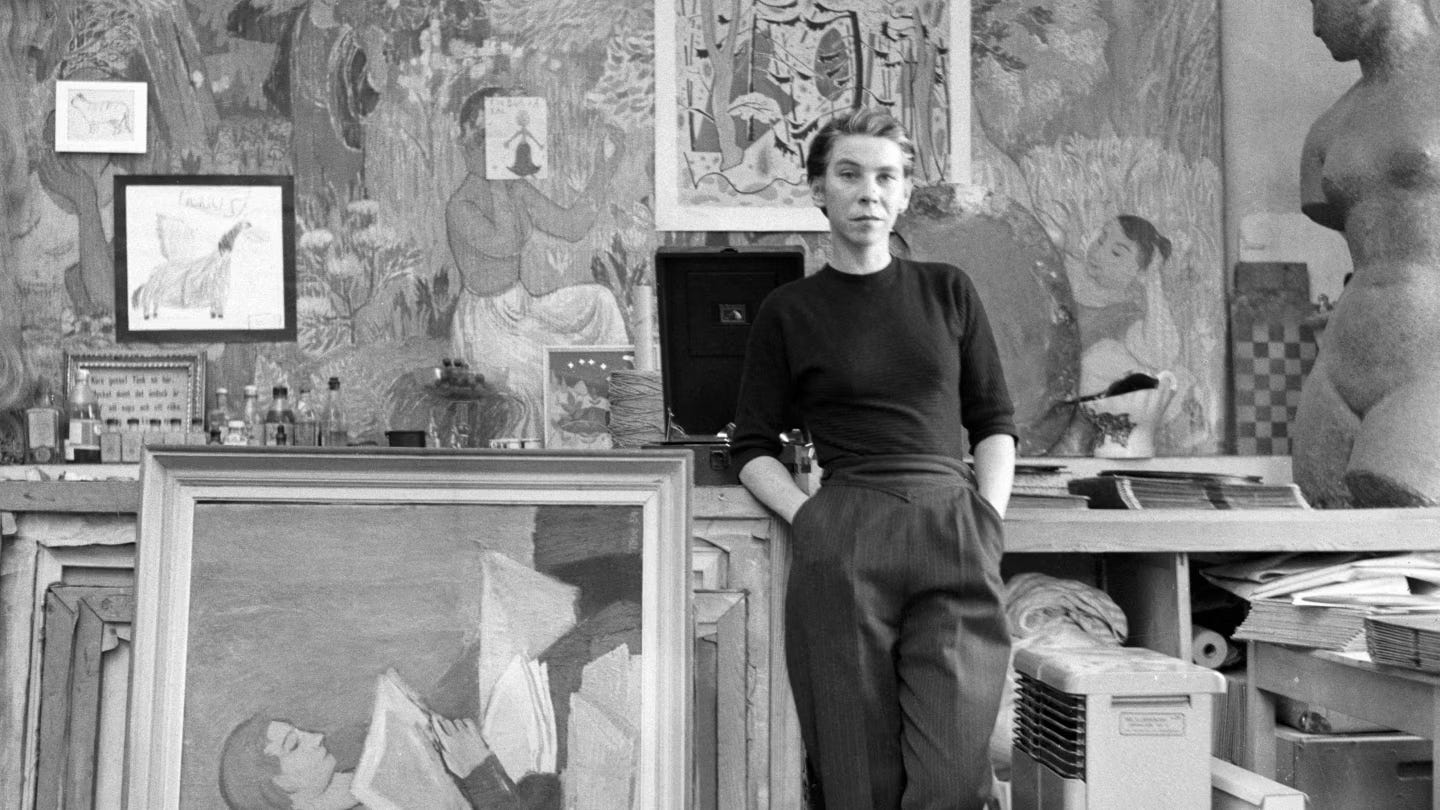

I’ve been reading the wartime letters and diaries of Tove Jansson, the Finnish artist and writer best known for her mid-century children’s series the Moomins. She’s not well known here in the United States; that’s our collective loss.

In the early 1940s, Finland was at war fending off the Soviet Union’s annexation attempts and aligned, for a time, with Nazi Germany — a compromised position borne of desperation and proximity that played out against the larger World War.

Jansson, then in her late twenties, lived through it all in Helsinki where she worked as a political cartoonist and recorded her thoughts in letters and diary entries.

In July 1941, Jansson wrote a Jewish friend who had fled to the United States: “The fact is that life is just waiting now, one isn’t really living, one just exists.”

Later that same summer, she tried to hold onto hope: “Deep down one firmly believes all will be well — that we’ll all meet again, that we’ll all be able to be happy.”

But in November, she sounded a more desperate note: “It’s as if the whole world has become a lump of anguish. I have never seen friendliness so mixed with bitterness, love with hate, and the will to live a good and worthy life so mixed with the pleasure of just getting out of the way and letting go.”

These contrasting pairs are woven throughout her wartime writings: friendliness and bitterness, love and hate, worthiness and withdrawal. Reading her letters, I found myself comforted by the way she acknowledged these ever-present contradictions.

“You have to either scream and quarrel or keep silent,” she wrote. “I’ve chosen to keep silent.”

Jansson may have chosen silence sometimes, but you wouldn’t know it from her outward work. While her brother was fighting on Finland’s front lines, Jansson waged her own battle — in cartoons.

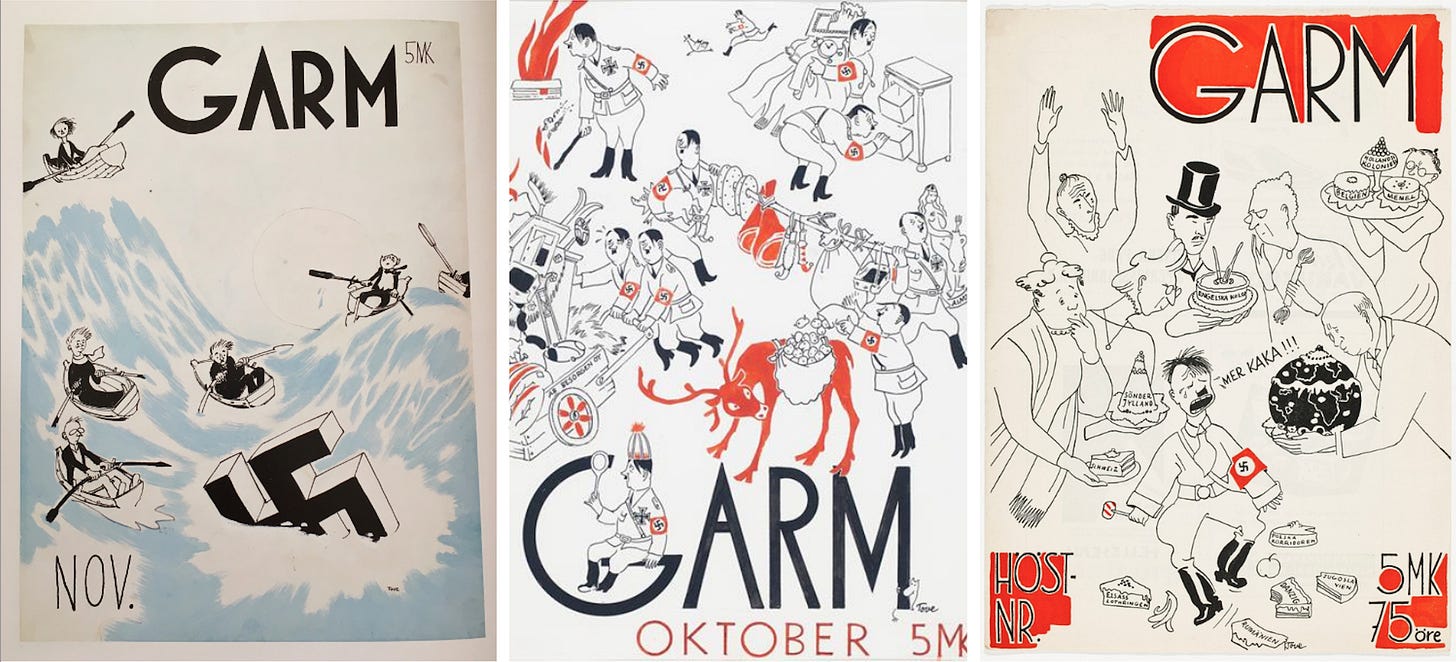

She designed hundreds of cartoons for the national magazine Garm. These were not warm and cuddly, like the later Moomins. These satirical cartoons were brazen attacks on Stalin and Hitler, at a time when Finland was still ambivalent toward the latter and it was dangerous to be an outspoken critic of either — the war’s outcome being uncertain.

Hitler was helping Finland fight that war; an ally for a time. For her attacks on Hitler, Jansson barely dodged prosecution for “insulting a leader of a friendly foreign power.”

Looking back on this period Jansson later wrote, “I enjoyed working for Garm, and what I liked best was being beastly to Hitler and Stalin.”

But this piece isn’t really about Jansson’s outspoken stands.

It’s about the odd familiarity of her accounts of herself and society.

She wrote of how the Finnish people became more entrenched on their respective sides instead of coming together, implicitly rejecting any whiff of contradiction in favor of all-in identities:

Pressed by the compulsion to keep silent, isolated by anxiety for their own little circle, each withdraws further into his or her shell. The great events around us, instead of broadening our vision, have contracted it to a petty obstinacy; in their panic, people firmly fix themselves to the misguided terminology of nationalistic slogans; boundaries became ever more inflexible and logic goes out of the window. The old principles and prejudices are asserted ever more widely. In this chaos of monologues contact becomes completely impossible with a people who even before were incommunicative and stubborn.

That could just as equally describe how people in the US and elsewhere reacted to pandemic fears by retreating further into tribalism and scapegoating. It’s only gotten worse since then. Why understand the other side when you can condemn?

The connection came to mind because Jansson’s description of wartime polarization in Finland evoked Naomi Klein’s incisive treatment in Doppelganger of how the pandemic’s anxiety produced the same dynamic in our time.

Jansson also wrote on a personal level about the continuous dread buried beneath her surface persona:

As things are, anxiety grips me; even though from the outside I might seem to be living an ordinary daily life, working as usual — if I feel happy, there is always a dark, burrowing background of anguish and a mass of gruesomely clear images in the imagination that are not always easy to chase away.

This is just what I was describing at the start — those two planes of living.

What comforts me about Jansson’s writings is a sense that contradiction is normal in these freighted moments. It’s natural to feel torn, sometimes to “scream” and sometimes “keep silent.” This is the reality of trying to live an ethical life under strain.

More than once she wrote of ignoring the news, of keeping the radio off, of avoiding the telephone. “They dig up everything that’s smouldering and burning deep inside you,” she said.

I’ve done the same these past years, a kind of hiding that feels cowardly. Not because I don’t care; because I care too much, and there’s only so much you can take. Jansson’s example shows me that on a historic scale, that’s a normal reaction to societal crisis, which makes it feel more OK.

Jansson’s writings have lingered in my mind. Not because they offer clarity on today’s (very different) events — they don’t — but because they mirror the confusion and anxiety many of us feel now.

I’m reminded of Anne Helen Peterson’s recent piece “The World Has Always Been on Fire.” She explores many ideas about our current societal and historical moment, and there are convergences with Jansson’s writings on the theme of contradictions and contrasts.

Peterson rejects the idea that “creating art in dark times is somehow inappropriate — or evidence of a lack of commitment to justice.” We don’t have to be all one way or another, just as Jansson wasn’t in her decision at times to scream and at others to keep silent. We don’t have to flee contradictions, like writing about “romance or frivolity or joy or fantasy” (Peterson’s words) when we also feel despair. We can live with contradiction; we need to live with contradiction.

By accepting contradiction we can make progress. “If a burning world is our lived reality,” Peterson asks, “how do we continue to steer ourselves towards the sort of compassion that might create a different one?”

The answer, she says, is not to “police” each other or “parse others’ good-faith posts for ill-intent.” I find myself wanting to pause there. Because Petersen quickly moves to clarify — to defend the point — by adding that she’s “not saying make friends with fascists.” But I wish she had stayed longer with the original claim: that we don’t need to parse and police to move forward with our principles.

Because I think that’s another aspect of living with contradiction. That just as we can be OK with our contradictory insides, we can be OK with contradictory outsides, too. What happens when we openly acknowledge that we disagree and agree with the same person on different issues? What happens if we remain allied with a person who says things that are “right,” but also says things that are “wrong”?

What’s at stake when we demand perfection and consistency is stagnation versus movement. When we accept contradiction in ourselves, we don’t get stuck trying to fit into a single shape. When we accept it in others, we can sidestep the subplots and skirmishes that keep us circling the same ground. Being OK with contradiction means avoiding the all or nothing trap that keeps us glued to one place. Paraphrasing Peterson, we can use our energy to move with clearer purpose in the direction of the world we want.

Let’s reject purity tests in all forms; they’re insidious no matter the context. Perfection — and its cousin, consistency — are not realistic goals for any of us.

There’s no tidy resolution here, which may be just as well for a post that’s mostly about contradiction. Jansson’s writings give us something other than clarity: recognition, permission, and an invitation to acknowledge the contradiction and keep going.

For more on Tove Jansson, an extraordinary person, I can’t recommend highly enough Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words by Boel Westin.

Did you enjoy this post? Please support for my work (for free!): Subscribe for regular updates and tap below to heart this post so others discover it.

Looking for more to read? Check out these past posts: