The "god trick" and how we read authority

Against the view-from-nowhere: speaking with location, limits, and responsibility

Donna Haraway’s “god trick”—a voice that speaks from nowhere while claiming to see everywhere—is one of the most useful concepts for thinking about authority and objectivity that I’ve encountered. In this essay I apply her framework against Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author,” and see reverberations in everyday gendered discourse.

Read on…

I used to abandon my judgment too quickly. If a pronouncement wore the right costume—confident tone, institutional sheen, vocal adherents—I let it tell me what was true, even about things that were plainly arguable. That mantle of authority can be hypnotic: it invites you to put down your skepticism and pick up someone else’s certainty.

In this newsletter: Roland Barthes’s influential “Death of the Author” ⁕ claims of objectivity ⁕ Donna Haraway’s “god trick” ⁕ feminist science ⁕ literary criticism ⁕ Joseph Conrad on the link between novelists and scientists

I would tell myself, I can trust this person—even more than myself. The gap between what I thought and what the author declared became proof that my instincts were flawed. I learned to treat my internal compass as unreliable because it diverged from what arrived in sleek official formats.

But for a variety of reasons, as I’ve grown older, I’ve started to distrust that mantle of authority and to recognize that my instincts have value.

Writing here on Substack is part of this emergent recognition. I still hesitate to offer pieces that are strictly matters of opinion, because who should care about my opinion? Yet I feel with each piece I’m growing more confident, less tentative.

A byproduct of this newfound confidence to push back on the intellectual authorities is that I have a lot of catching up to do. Allowing myself freedom to challenge entrenched ideas means I'm seeing things to challenge everywhere, mostly in the past.

The world has moved on yet I'm knocking on the door saying, I heard there’s a party here. Meanwhile the place has changed tenants three times. I’m arguing with ghosts.

Often, while reading texts, I feel a sharp reaction to that brand of self-assured certainty I described above. I bristle at pronouncements on genuinely debatable matters that proceed as though no justification is necessary. I get irritated, because I know how stifling that posture is for people (like me; like women; like people with mental “disorders”) who are made to justify their views by society.

Barthes’s influential essay “The Death of the Author”

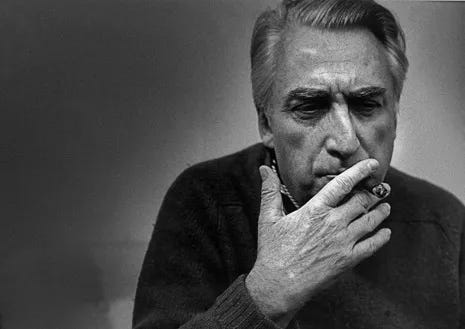

Here’s a ghost I’ve been arguing with recently: Roland Barthes’s 1967 essay “The Death of the Author.” For decades it’s been taught and admired because it seemed to free readers from the obligation to consider what the author of a text intended the text to mean.

Barthes’s claim in the essay is simple and sweeping: the modern cult of the author has trained us to hunt for a single, authorized meaning—whatever the author supposedly intended—and to treat all other readings as mistakes.

There is a kernel of a useful corrective there. But Barthes goes much farther than offering a corrective in his essay. He enacts a law.

I not only disagree with most of Barthes’s assertions in the essay, which I’ll write about elsewhere, but I’m repelled by his manner of asserting them.

He never uses “I think,” but only “we know,” indicating there is only one possible view. His assertions are unequivocal; there is no nuance, just an all-or-nothing choice. A right way and a wrong way. This authoritative tone reaches its zenith in the concluding sentence:

We are no longer so willing to be the dupes of such antiphrases, by which a society proudly recriminates in favor of precisely what it discards, ignores, muffies, or destroys; we know that in order to restore writing to its future, we must reverse the myth: the birth of the reader must be requited by the death of the Author.

This sentence universalizes a personal stance—Barthes’s—as a mandate.

The god trick and situated knowledge

My instinctual aversion to this kind of writing was reflected back to me when I encountered Donna Haraway’s brilliant 1988 essay, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.”

Haraway, a founder of Science and Technology Studies, names in this essay the rhetorical posture I’ve been reacting to. She calls it the god trick: speaking from nowhere while claiming to see everywhere. A disembodied voice, belonging to a person who feels no pressure to situate themselves as a specific person. No impetus to acknowledge their subjectivity, because authority is their natural and proper state.

This pretense of an all-knowing, all-seeing perspective—a universal view—is a trick.

She asks us to consider the metaphor of glossy space photos presented as reality. Here is the Milky Way, a magazine says, gesturing toward an image.

But there’s no neutral view: even in the realm of photography, an image is not an unassailable depiction of reality. Each image is the product of particular instruments, choices, and positions. These are all mediations—things that come between Reality or Truth as it’s being presented and us, the viewers. The trick occurs when a speaker pretends that these mediations don’t exist.

Although an authority figure may claim to show us the Milky Way—equivalent to Barthes’s action in declaring that the Author-God must be killed to properly interpret texts—in truth, an authority figure can offer only a specific lens. A reality bounded to a single perspective.

Claims that arrive shorn of context—no method, no standpoint, no “here’s how I got there”—ask us to treat a partial view as universal. And that’s where trouble lies.

Haraway’s point isn’t “nothing is real.” It’s this: if you want to claim objectivity, you must show your work. Tell us where you’re standing, what tools you used, what you left out.

As she puts it:

There is no unmediated photograph or passive camera obscura in scientific accounts of bodies and machines; there are only highly specific visual possibilities, each with a wonderfully detailed, active, partial way of organizing worlds.

Haraway’s key insight is that “only partial perspective promises objective vision.”

Partial perspective is an accountable vision—one you can call to account because you’re engaging not with a vague voice with no point of origin (with which discourse is, of course, impossible), but with a specific voice coming from a specific location.

Haraway calls this situated knowledge.

Applying the god trick to literature and lit criticism

Although Haraway’s particular focus is scientific discourse, I believe the same god-trick framework can apply to literary discourse, which was Barthes’s terrain.

While some fiction presents itself as simple entertainment, many authors claim a deeper purpose: to reveal the truth about our present reality.

Consider Joseph Conrad’s argument that the fiction writer aims, like the scientist, to reveal “what is enduring and essential” about the world:

A work that aspires, however humbly, to the condition of art should carry its justification in every line. And art itself may be defined as a single-minded attempt to render the highest kind of justice to the visible universe, by bringing to light the truth, manifold and one, underlying its every aspect. It is an attempt to find in its forms, in its colours, in its light, in its shadows, in the aspects of matter and in the facts of life what of each is fundamental, what is enduring and essential—their one illuminating and convincing quality—the very truth of their existence. The artist, then, like the thinker or the scientist, seeks the truth and makes his appeal.

I find Conrad’s description of the novelist’s project to be valid. Novels do circulate as social knowledge; they shape what readers take to be plausible or typical about people and places and causal relationships.

If we follow Barthes and kill the author, then, contrary to his argument that we’re killing a “God,” we’re actually performing an apotheosis. We’re pretending that the view the text provides is a universal one—the Milky Way—as opposed to a specific vision of the world tied to a specific author’s lens.

The god trick, then, lends a conceptual counterargument both to the way Barthes expresses his views in “The Death of the Author,” and to the views themselves.

The god trick as a feminist philosophy

Haraway, an influential feminist who transformed the philosophy and history of science, tackled all this from a feminist viewpoint. The god-trick had led certain voices to be marginalized and excluded in scientific discourse, including voices of women.

But what I love about her essay is that she doesn’t do the thing that Barthes does in his. He replaced one myth with another by toppling the author and enthroning the reader. Haraway’s handling of her issue is far more nuanced.

To be sure, Haraway offers a qualified argument that marginalized viewpoints should be privileged. But this is not as a matter of reparation, or vengeance, or some sort of ascendancy of the downtrodden.

Her argument is based on reason. We should prefer perspectives from “below” (that is, from the position of subjugated, marginalized people), she says, because they’re less likely to perform artificial objectivity. Less likely to buy into the god trick and perpetuate it. They’re not more likely to be right, but they’re less likely to deceive us into believing they’re right. And thus, they more effectively advance discourse.

Consistent with this careful take, she warns against romanticizing marginalized viewpoints.

“The standpoints of the subjugated are not ‘innocent’ positions,” she writes. They are authoritative only when they stay answerable—open to critique, method, and mediation—rather than claiming a disembodied right to speak for all and without challenge.

Thus, her god-trick warning cuts in both directions: against the powerful who pretend to speak from nowhere, and against any of us who might smuggle in a new kind of untouchable authority under a banner of marginalization.

Extending Haraway’s argument outward to everyday discourse

Haraway’s theory helps me understand why the no-excuses, no-questions-asked authoritative tone taken by Barthes and others grates on me so much.

It also, I think, points to why women and other marginalized people are more likely to notice and be distracted by such tones of voice, even to the point, as in my case, of irritation.

In Western culture, the performers of the god trick have been traditionally white men. Let me be careful here: Not all white men communicate this way, but of the people who do, they have been more likely to be white men.

Other categories of people may internalize that this style of discourse is unavailable to them. I certainly did. Women start emails more often by saying “I’m sorry,” or are more likely to qualify their views with “I think” and “I believe.”

Society has traditionally seen this manner of speaking as a negative tic that should be fixed. But there’s another way to see it. I think these qualifiers support Haraway’s argument that marginalized people, such as women, are less likely to perform the god trick. Which is a good thing.

I also see a link to the concept of “mansplaining”—that presumptuous, superior way of explaining things. Men do this to each other all the time (I’ve observed it with interest), but it rolls off other men like water off a raincoat. For those of us not used to wielding that kind of conversational authority, it soaks in and weighs us down.

A counterpoint to Barthes: the partial perspective of Wayne C. Booth

While working on this essay, I happened to be reading The Rhetoric of Fiction by Wayne C. Booth, a foundational literary criticism text that examines how authors communicate their views to readers.

Booth, like Barthes, was highly influential in the field of literary criticism. They were contemporaries; The Rhetoric of Fiction was published in 1961, six years before Barthes’s essay.

While reading, I noticed how Booth’s style avoids the godlike stance of Barthes’s, and how nourishing that feels to me as a reader.

For instance, Booth wrote in the book’s Preface:

The fun will come in testing what I say, not against any given theory you have learned, but rather against your own experience of Boccaccio’s “The Falcon,” of Porter’s “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” of Joyce’s Portrait, of Austen’s Emma—of whatever story you have recently enjoyed and would like to recommend to me.

Here, Booth is acknowledging his partial perspective, one that the reader can “test” themselves. And he’s going further. He’s admitting that the canonical works he uses to illustrate his theories are not authoritative. The reader can not only disagree with Booth’s views, but also with the selection of stories that supply the testing material. He demonstrates his openness by acknowledging that the reader has the authority to recommend their own examples to him.

I like it when someone converses with me in this way. They are meeting me more truthfully, more directly, with less pretense. Yes, it turns out being more verbose (by inserting “I think” and “I believe,” by devoting a Preface to the limitations of your book’s analysis) can amount to being more direct, because you’re making explicit what’s not always implicit. These are thoughts and beliefs that I have, and I recognize that others may not share them.

So here’s the essential point: To reverse the harm wrought by the god trick, we should keep the makers and the making of text in view. We shouldn’t pretend that text speaks from nowhere.

If the god trick is the seduction of placeless certainty, then the antidote is modest, locatable confidence: here is where I’m standing; here are the methods I used; here is what I can and can’t see.

Otherwise, all we have are voices shouting into the air, untethered and unaccountable.

To take a highly unscientific poll, I’m curious—do you notice and react when a writer uses the god trick? Alternatively, do you notice but not mind, or perhaps not notice at all? And of course, I’d love to hear your other thoughts and reactions to these topics.

Did you enjoy this post? Ways to support my work—for free!

1. Subscribe for regular updates and 2. Tap below to heart this post so others discover it.

Looking for more to read? Check out these past posts:

Stay curious,

Laura

Yeah, people often ignore that scientific discoveries are group efforts and tend to try to pin inventions on 1 person suddenly getting 'inspired'.

It's interesting to contrast Barthes and Booth. I tend to use "I think" and "I believe" a lot in my writing. This article makes me feel better about that...