Setting the scene: how visuals and memory intertwine in autism

Why difficulty with scene construction may block memories of life events

In my last post, I described the feeling of “losing access” to parts of my life—of relying on others to fill in memory gaps, especially emotional and narrative ones. I now know these autobiographical memory deficits are common in autism.

But we haven’t talked about the reasons for it. Why do these life memory deficits exist?

Since social processing is different in autism, you might theorize that we can’t remember life events because they’re expressions of the self—and more specifically, the social self.

Contrast your birthday celebration at age 9 with the fact that earth has four layers, which maybe you learned around the same time.

The former is an instance of autobiographical memory (a blend of semantic memory that relates to yourself as well as episodic memory of personally-experienced events); the latter is semantic memory alone (semantic memory is mostly just factual information, like state capitals or why composting is good for soil).

I’m far more likely to remember that the earth’s core is liquid1 than how I celebrated a birthday. (Writing this, I realize I can’t remember any specific birthday celebrations before age 13).

Research supports the social-deficit theory, and also points to sense-of-self deficits as the culprits.

For example:

In 2020, researchers found that people with autism (without intellectual disability) tend to have a fuzzier sense of their own identity. They also found that autistic people were less likely to use autobiographical memory for social purposes, like sharing stories. They suggested that these findings explain why autobiographical memories—especially socially significant ones—are harder to access than factual knowledge.

In 2017, another study found that autistic adolescents (without ID) had trouble recalling both components of autobiographical memory: semantic facts about themselves (like personality traits) and personal experiences (especially ones with emotional detail). The researchers suggested that differences in how autistic people process self-knowledge may help explain why some memories—particularly those with emotional or social meaning—are harder to retrieve.

Explanations rooted in self and social relationships would explain why I can’t remember specific conversations during my birthday celebrations, or even who attended them.

Yet I also don’t remember where these birthdays took place, what the themes were, what kind of cakes I had. Those are semantic memories: facts. It’s not obvious why birthday-related facts are irretrievable, when I can remember random facts unrelated to me (like most—but not all!—of Henry VIII’s wives).2

Which is why a recent research review suggesting an additional explanation is particularly interesting.

In 2023, a review of multiple studies proposed that an altogether different challenge may explain autistic autobiographical memory challenges: scene construction.

This refers to the ability to mentally recreate the visual experience of an event: what the place looked like, how things were arranged. For instance, researchers have found that even when social or self-specific elements were stripped away (like imagining a fictitious beach or museum), autistic people described scenes with less vividness and spatial detail. The same was true for the real events of autobiographical memory; the challenges spanned both kinds of scene visualization.

This suggests that scene construction deficits may help explain why specific events from personal memories are hard to access.

This problem may also affect future thinking and spatial navigation, researchers theorized, since those skills also rely on imagining detailed scenes.

(Some anecdata to ignore at your leisure: I’ve always been known within my family for having a poor sense of direction. I get lost or disoriented easily. The correlation between spatial navigation and autobiographical memory holds up in my particular case—I have challenges with both.)

Even when given strong prompts or visual cues, autistic participants still recalled fewer sensory and spatial details than non-autistic people.

To be clear: the scene construction theory isn’t a replacement for existing explanations. The researchers argue that it is distinct from—but likely interacts with—social and self-related differences, offering an additional explanation for why autistic people may struggle to recall specific life events.

Why was this overlooked previously?

This is one of the most interesting parts of the theory, because it demonstrates how advanced technology can reveal that earlier conclusions may have been incomplete or based on flawed data.

Our brains’ “social” and “scene-construction” networks sit right next to each other. Which may explain why researchers previously overlooked this spatial dimension of memory in autism.

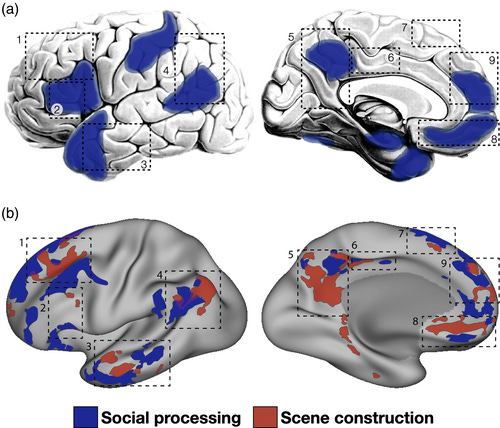

Take a look at this graphic:

The brain regions shown in (a) are the “canonical social processing regions, defined from large-group studies.” They are frequent targets of autism research.

The regions highlighted in (b) were more recently identified through advanced brain imaging, fMRI. This enabled more precise location targeting, and it reveals that “social regions (blue) are adjacent to, and often interdigitated with, regions involved in scene processing (red), with little apparent overlap (purple).”

If you compare the (a) and (b) images, you’ll see that some regions thought to be social processing are actually used for scene construction, not both.

The study goes on to observe that although the red and blue regions are functionally distinct (as shown by the dearth of purple, the overlap), “the two networks can nevertheless be difficult to disentangle at the group level.” That is, group-level research might mistakenly attribute a mental process to a social region of the brain because it wasn’t able to pinpoint the highly specific scene construction brain location at work, a mere hair’s breadth away. Averaging across brains blurs the resolution needed to distinguish between closely adjacent regions.

With that, I’m curious: if you identify with poor autobiographical memory, what’s your experience specific to scene construction—for instance, spatial navigation?

As for imagining spaces, like the museum and the beach in the example, the findings were that autistic people had deficits on a relative basis (their scenes were less vivid and detailed than those imagined by non-autistic people), which is hard to form the basis of a self-report. But if you have insights on that as well from personal experience or otherwise, please share!

PS: Are you starting to feel like I post about deficits too much? I am too. The cool thing is that deficits are sometimes one half of an evolutionary trade-off, freeing up brain resources to create strengths in other areas. I’ll explore that aspect in future posts.

Did you enjoy this post? Ways to support my work—for free!

1. Subscribe for regular updates and 2. Tap below to heart this post so others discover it.

Looking for more to read? Check out these past posts:

Research cited in this post:

Romain Coutelle, Marc-André Goltzene, Eric Bizet, Marie Schoenberger, Fabrice Berna, Jean-Marie Danion. 2020. Self-concept Clarity and Autobiographical Memory Functions in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder Without Intellectual Deficiency. J Autism Dev Disord. 50(11):3874-3882. Read online.

Sally Robinson, Patricia Howlin, Ailsa Russell. 2017. Personality traits, autobiographical memory and knowledge of self and others: A comparative study in young people with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 21(3):357-367. Read online.

Anna M. Agron, Alex Martin, Adrian W. Gilmore. 2024. Scene construction and autobiographical memory retrieval in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research 17(2):2024-214. Read online.

Stay curious,

Laura

Ed. note: A pre-publication fact check reveals that only the outer core is liquid. Error retained for transparency. Sometimes, my memory is just faulty all around!

OK let’s see… there’s Katherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, Catherine Parr, Jane Grey Seymour. [Ed. note: my memory fails are on full display today. Thanks Alys!] That’s all I got. Who’s missing? If you can remember without looking it up, drop the name in the comments! No prize other than my admiration.

Without looking it up, wasn't Jane Seymour married to King Hank 8?

I will look at pics others took of me at some event - like birthday parties - and it doesn't really seem real to me. I mean, I know that kid there is me, and there? isn't that one of my friends from 5th grade? When I look at old pics, I either don't remember a damned thing, or the photo makes me feel some sort of very vague memory recovery. Add maybe to this: I don't like looking at pics of myself. Never have. I don't like mirrors much, either.

Also: my sense of direction is horrid, but I will remember specific times when I got lost, probably because I reflected on the event. I realize I must have taken a wrong turn. I try to get back on track/find the way and it's not correct. Then: a sort of anxiety, even panic, which I suspect adds to the memory. Finally: I find the way. I have no problem asking strangers for directions.

I know there's GPS now. I prefer not to use it, which I think must sound perverse, given my admitted poor sense of direction. I make a physical map or a list of sequential moves I must make in order to get there, and I keep it on the passenger seat. I strongly identify with "that big maple tree" or "just past the Burger King" or "that old run-down Victorian" or "the really hideous off-ramp area" much more so than names of streets. Also: if there is a mass of large buildings as in big cities, and mountains, things "look" correct based on their relationship to these visual touchstones. Once I've been to a place, I remember how to get there, because it "looks this way when you go that way." But if I haven't taken that route for a few years, I will tend to forget it just enough to (probably) get lost at least a little bit.

Other minds: we can't know them, but we can infer from what they say and relate via perceptions and personal memory retrieval. I've long suspected most people have far better social memories than I do.

Thanks for your knowledge about social memory. About myself, my language tends to be more like "I think I'm the sort of person who..." rather than "I am the sort of person who..."

I wrote a whole other comment about your post, and must not have pressed send!?

It said something like: sorry for jamming up your whole comment section 🤣 but this would explain why the only autobiographical memories I have are ones there are photos of - I might remember a few additional details about an event, other than what's in the photo, but not much.

Also, it explains why I'm terrible at picturing things like, what a room will look like when it's decorated, or with the furniture moved around. And why I'm no good at writing fiction.... I knew there was a reason 😜🤣