My autistic special interests: the fire that burns itself out

On the electric pull of special interests – and a crash that always follows

Ever since my diagnosis, I have not stopped riffling through memories and behaviors to reconsider them in a new light. In my free time, I’ve been voraciously reading everything I can get my hands on about autism.

I recognize this state. It happens every time I start a new project, and there have been many such starts!

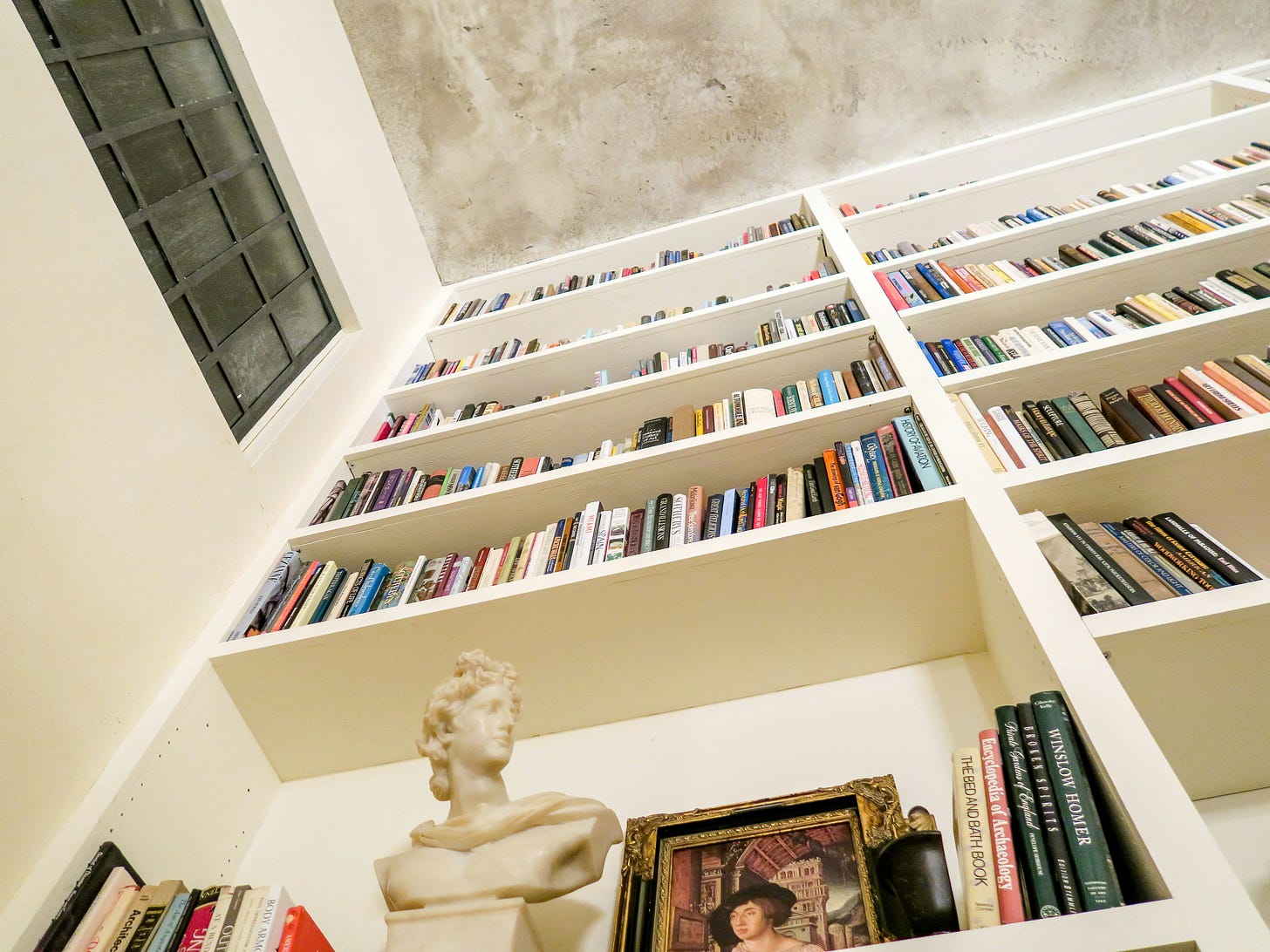

Past fixations have included portrait drawing, sewing clothes, and screenwriting. They range from the highly general (bread-baking) to the highly specific (translating the 20th-century horror stories of a little-known Argentinian writer).

This cycling through intense fixations is a variation on the autism-defining “special interest,” a trait first documented nearly a century ago.

Soviet psychiatrist Grunya Sukhareva, one of the first to describe the modern profile of autism, observed in the 1920s that her patients often had highly specific, intense interests that they pursued with remarkable focus and depth.

These were distinguishable from mere hobbies. For instance, the patients had a particular focus on details. And some children displayed an exceptional ability to absorb and retain information about their interest, often at a level far beyond their age. Plus, their desire to engage with the interest was particularly strong. They demonstrated distress if they were forced to shift focus.

The trait was initially thought to be an avoidance mechanism, a way for autistic people to retreat from external stress.

Researchers now understand that the special interest is a reward in itself.

Special interests often survive into adulthood. (Cue Reddit post: “I just found out about my Autism and now my special interest is Autism.”)

In a 2014 study of 76 adults with Asperger syndrome, participants reported that they spent an average of 26 hours per week on their special interest.

A fascinating 2021 article in The Transmitter collects stories of childhood special interests that turned into lifelong careers. Mariana de Niz, for instance, grew up in 1990s Mexico City, where a cholera eradication campaign ignited an intense fixation on pathogens.

“Sort of obsessed,” as she put it, she followed that passion all the way to her current role as a research professor in Cell & Developmental Biology at Northwestern University.

“She is known for making compelling images that require a degree of patience some of her colleagues say they could never muster,” the article reports, adding:

She often spends hours following a single T. brucei and capturing its most ephemeral movements. She gets so absorbed in the experience that she often forgets to eat, and her ophthalmologist says she is wearing out her eyes.

I can relate. I regularly skip meals when a project takes hold, and my personal care routines start to slip. (The fact that I work from home and am not forced to socialize in person doesn’t help.)

My lifelong pattern of deep dives into new pursuits was one of the first clues that led me to autism. Curious, I googled this aspect of myself, and found the connection.

Whereas some people with autism have a singular focus throughout their lives, like Tudor history or geology, I’ve never had a definitive special interest. Instead, I have a series of them, ranging in duration from three months to a year.

Nearly always, the project is something entirely new, where I lacked even a rudimentary knowledge of the thing to start.

When it was quilting, I began with the fundamentals – threading my machine, pre-shrinking fabric, precision-cutting pieces, ensuring seam allowances were exact.

For gardening, rather than just buy plants and put them in the ground, I read several books on landscape design. I created a design, then carefully selected varietals based on aesthetics, shade positioning, and native principles. Finally, I planted the garden, which at the end of it all, became overrun. Partly because of my strong aversion to late summer weather (I couldn’t weed in the blazing heat and sun), and partly because my interest had worn itself out.

Because each of my special interests follows a pattern: an intense learning phase, a peak of all-consuming engagement, and then just as suddenly… indifference.

I lose the hunger and abandon the interest without a backward glance.

This cycle is exhilarating, but exhausting. Having lived with the pattern for decades I know its arc well. I begin with the knowledge that I’ll likely never finish the thing I set out to do.

Pondering this cycle of continuous renewal, in which I pour significant effort and enthusiasm into a new project knowing it will end half-baked, I’m reminded of a passage from a favorite essay, “The Crack-Up” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. It describes the paradox of trying again when you know you’ll fail (in my case, a failure to see a thing through):

I must hold in balance the sense of futility of effort and the sense of the necessity to struggle; the conviction of the inevitability of failure and still the determination to "succeed" — and, more than these, the contradiction between the dead hand of the past and the high intentions of the future.

Fitzgerald was writing about something very different, but this perfectly describes the tension I feel when I think back on all the hobbies I’ve taken up and discarded over the years.

Despite all I’ve learned through my research, I’m still trying to account for the crashing part of my cycle. I don’t see it discussed in the autism literature, and it doesn’t line up with the concept of autistic burnout, either.

Autistic burnout has long been discussed within the autism community, but the first research conducted on the topic was not until 2020, at which time researchers defined autistic burnout as an all-encompassing state that is

characterized by pervasive, long-term (typically 3+ months) exhaustion, loss of function, and reduced tolerance to stimulus.

My form of burnout is not pervasive. It’s highly specific, affecting only my special interest. The other aspects of my life – work, caring for my kids, watching the TV show of the moment with my husband – continues as normal.

Perhaps the crashing of my special interests is a different phenomenon entirely. Or perhaps burnout exists on a spectrum, just as special interests and seemingly everything else related to autism does, and my form of burnout is one variation.

As I ponder what all this means for my current project – researching and writing about autism – the looming question is: If I come to a breaking point, like I have so many times before, how much will I get done before then? And will I ever return?

I’m encouraged that this time, a couple things are different:

First, I know I’m not alone. This isn’t just idiosyncrasy; it’s part of a neurotype. Maybe I can learn to harness this special interest cycling with intention and avoid the prior pattern.

Second, for the first time, I suspect my interest might produce something useful not just to me, but to others too; that there are people who might be interested in the perspectives I bring.

My internal motivation now has company: an externally-oriented motivation to say something out loud.

And so here I go again, setting out with the “high intentions of the future,” as Fitzgerald put it in that brilliant essay.

Thanks for reading Strange Clarity, where I write about neurodivergence, cognition, and the hidden architectures of thought.

If this post sparked something:

→ Leave a comment: even a simple “I was here” makes a huge impact.

→ Share it with someone thoughtful. Substack makes it easy.

More to explore:

🔍 My path to autism diagnosis: Why autism gave me supersonic hearing

🎁 My newest form of social challenges: Reflections after attending a four-year-old's birthday party

Prefer fewer emails? You can choose which sections to follow by clicking “Manage subscription” at the bottom of any newsletter.

Strange Clarity is reader-powered. If you’d like to support my work, the best way is to subscribe, comment, or share a post that resonated.

With curiosity,

Laura

Laura, ugh! I just want to say your Substack is one I look forward to reading. You're incredibly engaging and thoughtful, and I’m so grateful for the way you share your life and inner workings.

When it comes to losing interest in hobbies, I get it! Right down to the gardening. For me, the challenge of the learning curve is what keeps me hooked, but once the curve flattens and it’s all about maintenance, the interest fades.

There's just too much competing for focus, like eating regularly, getting some movement in, and connecting with humans outside of the house. They might seem simple for some people, but as an AuDHD, these are the things that are first to go when a new challenge presents itself. The struggle to maintain these basic components feels like a defunct.

Hi Laura, this is very thought-provoking! I, too, do this, but without so much self-awareness. I very nearly set out on training to be a midwife during my first pregnancy because I became so fascinated by birth! I also BECAME a full-time gardener after my special interest in flowers became all-encompassing. And only recently have I moved past an almost aversion to gardening that then followed...

I'm sorry to hear your beautiful garden was overrun, can you afford to pay someone to keep it weeded? I got an allotment and then was in allotment prison for a couple of years as I couldn't admit that I couldn't manage it/no longer had any interest in managing it. What a relief to finally get the letter of GET OFF OUR LAND.

I still have an aversion to growing vegetables. It's probably for the best that I never actually sold my house in order to go offgrid, lol.

What fun it is being this way! Happy to have found you, great post : )